By Colter Ruland

By Colter Ruland

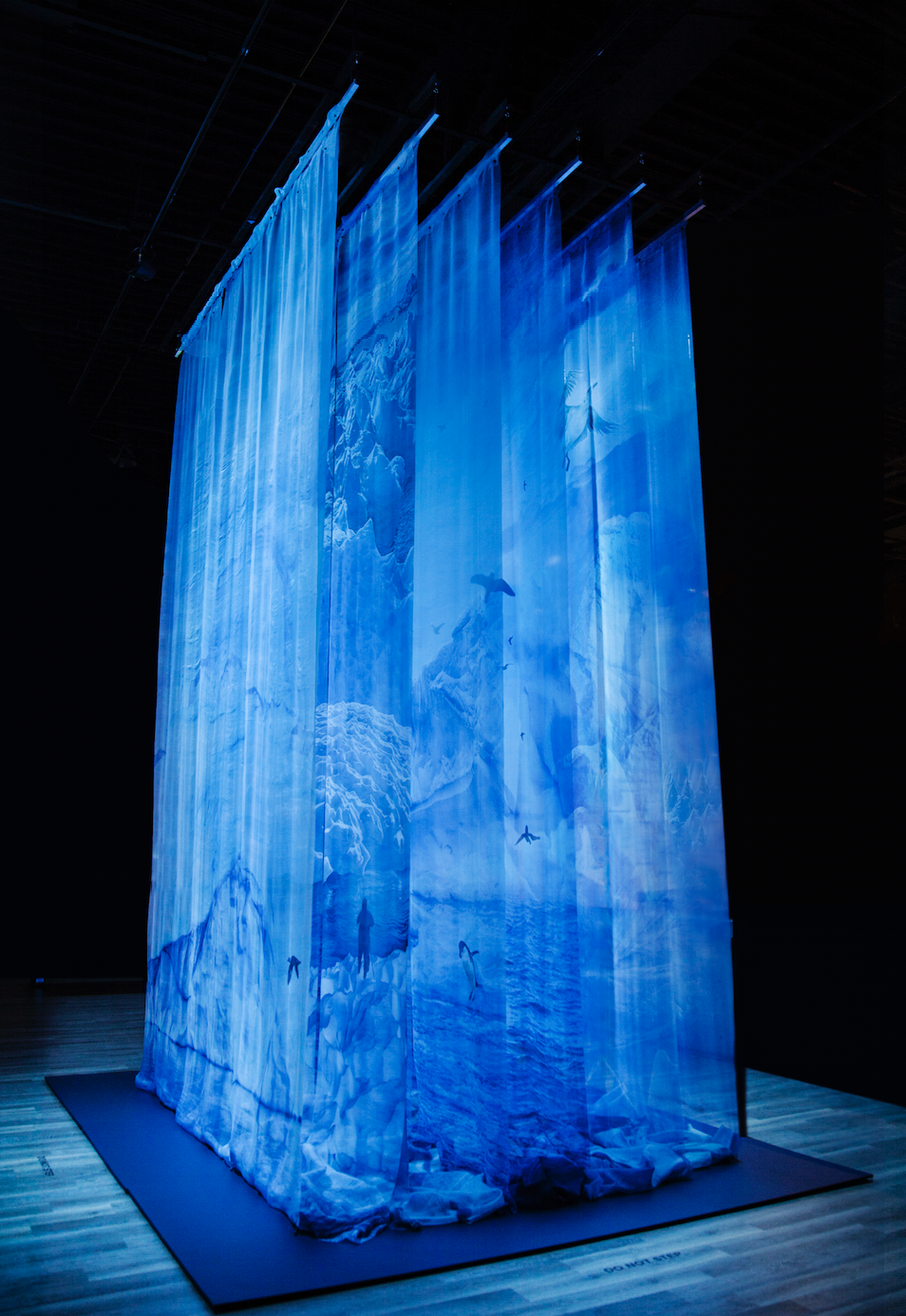

Patricia Carr Morgan is a Tucson-based conceptual artist whose most recent work aims to hold our attention on an overwhelming threat to our planet: climate change. After trips to Greenland and Antarctica, where she saw firsthand the devastating toll climate change has on our glaciers and habitats, Morgan returned stateside with a profound and stirring series of work that evokes the nature of loss. I asked her how she is continuing to make work during COVID-19, the role of art in times of unrest, and living in the desert.

The COVID-19 outbreak is on everyone’s minds. What role do you think you have as an artist when everyone seems to be panicking about events beyond our control?

My contribution as an artist isn’t any different from that of others. I wash my hands, I wear my mask, and I distance. It is important to remember that this will have an end and that for all of us, the work we do now will have its time.

Has self-isolation changed your creative process in any way?

Self-isolation without turmoil could be ideal. It is returning to a mental space where contemplation is possible that allows me to begin working again. My process hasn’t changed, but the process of getting there has become more complicated.

What have you been thinking about lately? What is driving you, creatively?

The pandemic, and now the horrible death of George Floyd, has occupied my mind. I’ve been learning about the medical and civil turmoil that surrounds us now.

The sense of danger and continued chaos is pervasive. My thoughts are about what might happen in the next 48 hours. With the pandemic coupled with the racial issues, I try to separate what I can control or influence from that which I can’t. I think about what help I might give in this locked-down position and then do what I can. When these catastrophic external events dominate every thought, there is no room for creativity. It is when I regain my ability to compartmentalize that my work begins again. My creative drive comes from the irrepressible need to work. Luckily, I’m currently working on a series that I think has importance, and that always helps move forward in difficult times.

Has the outbreak presented any specific challenges for you and your work? If so, what are they, and what can be done to create art in a time such as this?

Has the outbreak presented any specific challenges for you and your work? If so, what are they, and what can be done to create art in a time such as this?

Many artists are finding a way to lockout the virus and in the quiet of their studios, complete works and start new ones. For me, it has been more confusing. My pandemic piece expresses the sorrow and fear that was rampant, but it was deemed by my friends and me to be too horrific and lacking in subtlety to show. Someone in my family is at high risk, and I had been following death counts, disease counts, and counts of missing supplies. I retreated, and hopefulness and calm crept in as hand washing and temperature checks for visitors became habitual; we became accustomed to masks and gloves. More time in the studio is happening.

The quiet of the studio took me back to the place where my work starts. The preliminary “sweeping the floor,” or in this case, rearranging, filing, rolling and storing to make room for the new. These things gave my mind the freedom to roam and organize a path forward.

During times of national emergency, some might wonder about the relevancy of art in their lives. What do you think that role should be?

During times of national emergency, some might wonder about the relevancy of art in their lives. What do you think that role should be?

As an artist, I believe that with art, we guide people’s thoughts to places they’ve never been and hold new paths of discovery. The pandemic, now intertwined with racism and violence, makes life unbearable for many. Whether art offers an escape into beauty or tells us an awful truth, it can be a refuge or an awakening, but it’s always personal, for both the artist and the viewer.

What’s it been like being in the desert during self-isolation? For some reason, I imagine living in the desert as a kind of theoretical isolation as well.

The desert offers unending vistas, and with a glance down there is the discovery of intriguing and exotic details at our feet. You’re right, there sometimes is a feeling of isolation. However, Tucson is a medium-sized city with a prestigious university with over 40,000 students, so there are many events and activities. It’s also important to remember: the mountains turn cranberry red at sunset, and lockdown will not be forever. With trepidation, several years ago, I left my desert perch and moved to a “nest” that has recycled water for trees and flowers. It’s different, softer isolation and the mountains still turn cranberry red.

For an in-depth look at the exhibition of Blue Tears, please visit KUAT Arizona Public Media.

For more, visit her website here and be sure to follow her on Instagram @patriciacarrmorgan